"It's about life and death," Béla Kató told me recently. The Transylvanian Reformed Bishop (Romania) made this statement in an interview to the Online journal Válasz speaking about the institutional development program (of the Hungarian government) that is essential for the preservation of Hungarian and Christian identity in Transylvania, but it can be applied to the restitution of church properties in Romania, as well. Perhaps it is more correct to talk about non-restitution. Bishop Béla Kató and István Csűry, Bishop of the other Reformed Church District (Királyhágómellék) have recently been summoned to appear before the prosecutor's office, accused of, among others, forgery of official documents. According to Romanian officials, some of the documents necessary for the return of the building of the Wesselényi Reformed College in Zilah (such as the inventory record taken during the 1948 nationalisation) are supposed to be forgeries. Those who were born at the time when the legal process for reclaiming the ancient school in Szilágyság (Sălaj County) began, will come of age: the Hungarian Reformed community has been fighting for their right and property since 2003 (!).

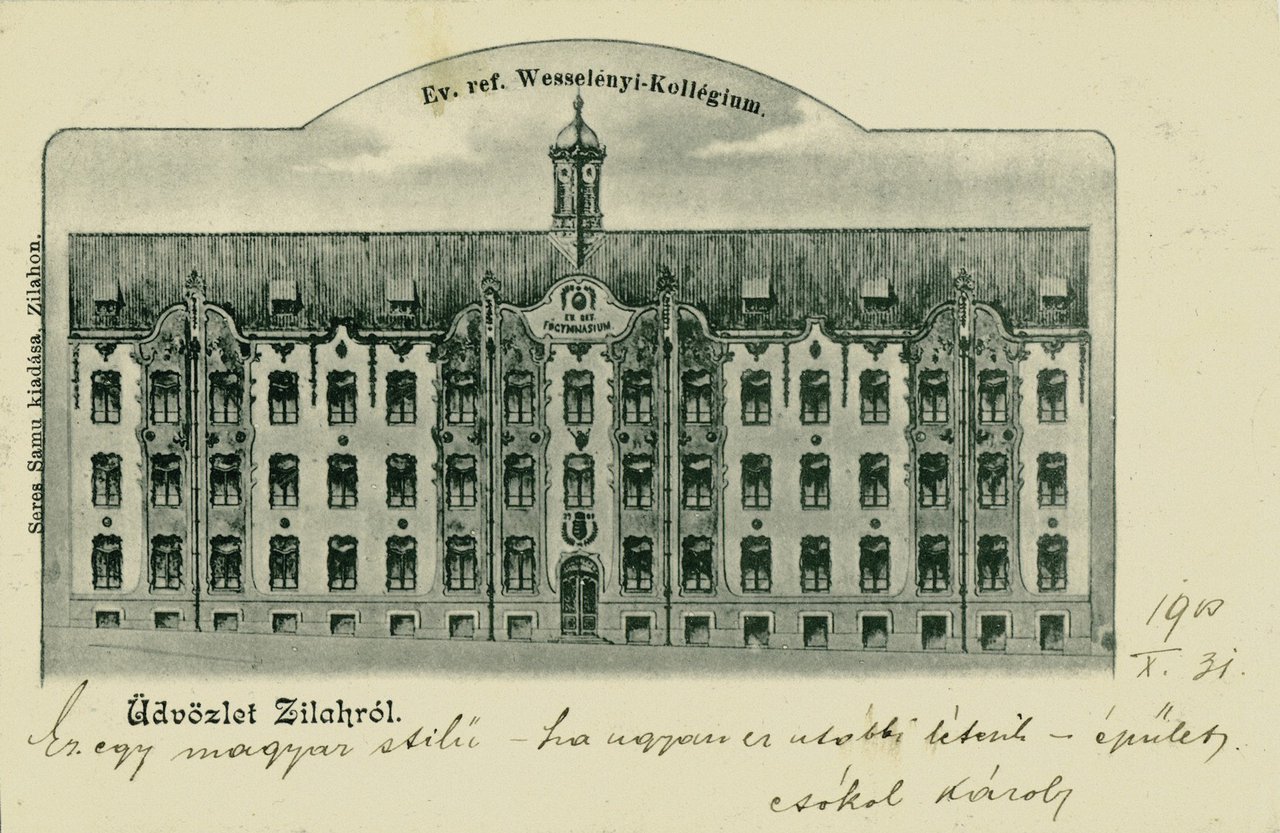

After many dead ends and legal wrangling, the church had a chance to reclaim the Hungarian style Art Nouveau building, which is now home to a Romanian lyceum, through a civil suit. According to the understanding of Béla Kató, authorities try to prevent the restitution process by playing the criminal card. The accusation of the court in Zilah is absurd, if only because since the re-nationalisation of the Székely Mikó College in Sfântu Gheorghe in 2014 at the latest, the Romanian state authorities have been alert and watching the court trials of the Hungarian historical churches Argus-eyed. Who would even think of submitting forged documents when it is known that they are controlled by all existing legal and political means?

One might shrug shoulders arguing that a single case does not allow us to draw far-reaching conclusions. But all the signs seem to support the assumption that restitution of Hungarian properties in Romania is no longer a legal issue, but rather a political one. Reference can be made not only to the College buildings mentioned above. Recently, the Romanian Supreme Court, on shaky legal grounds, definitively rejected the claim of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Gyulafehervár (Alba Iulia) for the restitution of the Battyáneum¸(Biblioteca Batthyáneum), the library and scientific collection founded by Bishop Ignác Batthyány in the 18th century. While it was legally returned to the Catholic Church in 1998, the Church was never allowed to take possession of it. One can be afraid that all the pending cases of the historic Hungarian churches in Romania are doomed to the same fate.

Wesselényi College in Zilah, 1903 - postcard

It seems highly probable that Romania felt forced to enact its relatively generous restitution laws at the time of NATO and EU accession out of necessity, and is now obstructing the process where it can. "Once the integration process was completed, we felt like the golden fish in the joke about a man who after catching it starts cleaning the fish. When he is asked why he were doing this, although he would have gotten three wishes, he replies: we have been through that already. The respective Romanian governments have already gone beyond their previous promises, and now they want to turn the clock back with all their might," says Béla Kató sarcastically.

It is no coincidence that the Romanian authorities have gone so far as to criminalise those who seek restitution exactly in the case of religious buildings, especially educational buildings. In Bucharest, it has been assessed that the future of the Hungarians in Transylvania depends mostly on their schools, since in the absence of quality mother tongue education, assimilation is only a matter of time. And the churches play a key role in running the Hungarian speaking school system in Transylvania. So, according to the calculation of the cold-heartedly political logic, it is the leaders of the churches who need to be prosecuted, and through them the whole community can be intimidated. The aim is clear, the machinery is in motion. Can it be stopped? This is the question.

The author is journalist, co-worker of the Church and Society Research Institute of the Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary

Transylvanian Reformed Church District Denied Restitution of Székely Mikó High School

Nine years ago, the Reformed high school was renationalized by the Romanian state, after which the Transylvanian Reformed Church District appealed to the Romanian Supreme Court. On 22 November 2018, the Court rejected the appeal to rightfully reclaim the school.

Originally published in Reformátusok Lapja, the Weekly Magazine of RCH.